By Kevin Brown

The civil rights movement propelled meaningful changes to the country’s tapestry in the decades following World War II. Alabama Army National Guard officer Henry Vance Graham was a witness who facilitated these changes during the Civil Rights era’s most heated moments in the 1960s.

Henry Graham was born and raised in Birmingham, Alabama. He enlisted in the National Guard during the Great Depression in 1934 and participated in responses to labor unrest in Alabama’s mining regions. Graham was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in September 1940 in time for the Great Maneuvers, which tested the US Army’s readiness for a global conflict; he then reported to active duty in November of the same year. A quote by Graham within the National Guard Memorial Museum illustrates his Great Maneuver experiences as a 2nd Lieutenant at Camp Blanding in Florida precisely a year before America entered the war. “The only things with a real roof on them for our company of 120 men were a mess hall and a latrine. Everyone was living in a tent.” [Notes by Maj. Gen. (Ret.) Henry V. Graham: On his Years in the National Guard of Alabama]

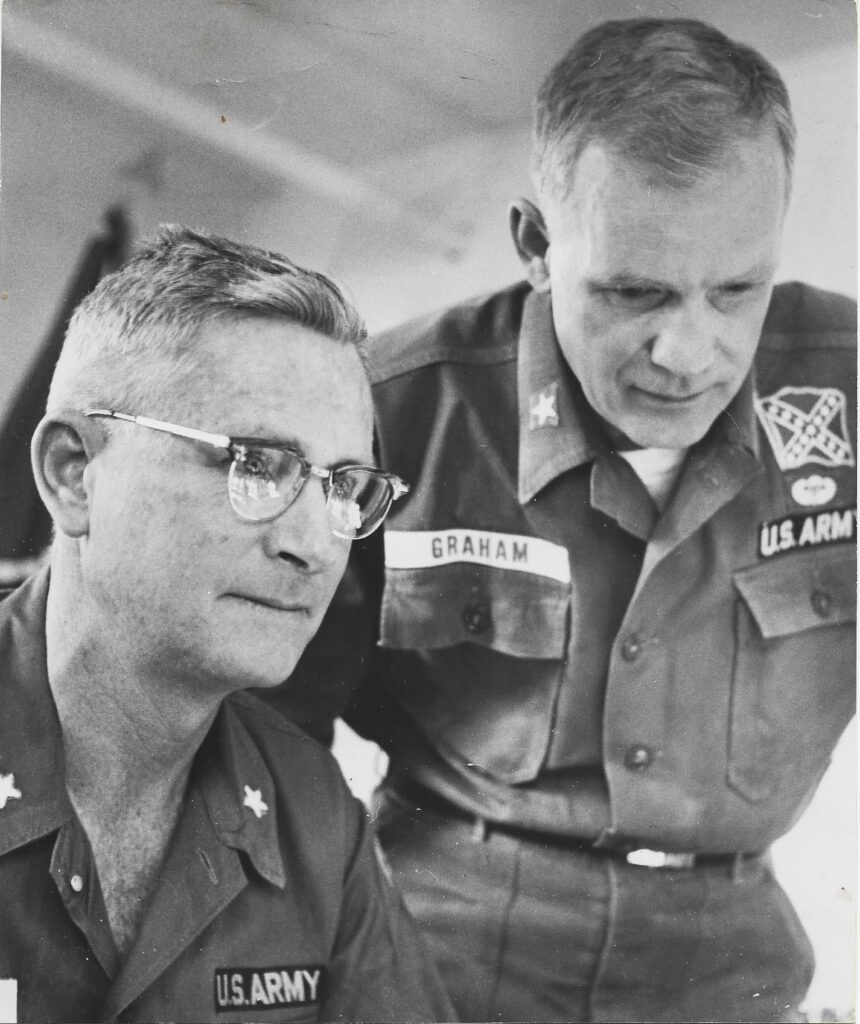

Graham served in the Army’s active duty, reserve, and National Guard components during World War II and the Korean War before transiting to the Guard full-time. He was appointed Adjutant General of Alabama in 1959 and Assistant Division Commander of the 31st Infantry Division in 1961, which left him federally recognized as a Brigadier General but holding the state appointment of Major General until he left the office of the Adjutant General in 1963.

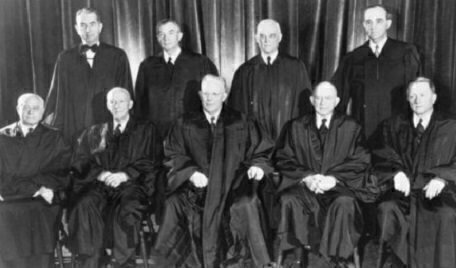

National debates over racial discrimination and segregation quickly heated as Graham’s Alabama National Guard career progressed. In 1954, the Supreme Court issued its landmark decision in Brown vs. Board of Education, finding segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Chief Justice Earl Warren stated, “We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place, and separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Southern governors quickly pushed back on the Supreme Court’s decision via a “massive resistance” policy to Federally mandated integration efforts. These efforts included governors utilizing the National Guard to enforce segregation in defiance of the federal government. Arkansas governor Orval Fabus mobilized his state’s National Guard in 1957 to block integration efforts in Little Rock. [The National Guardsman: Oct 1957] Massive Resistance led Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations to federalize the National Guard to remove obstacles to integration.

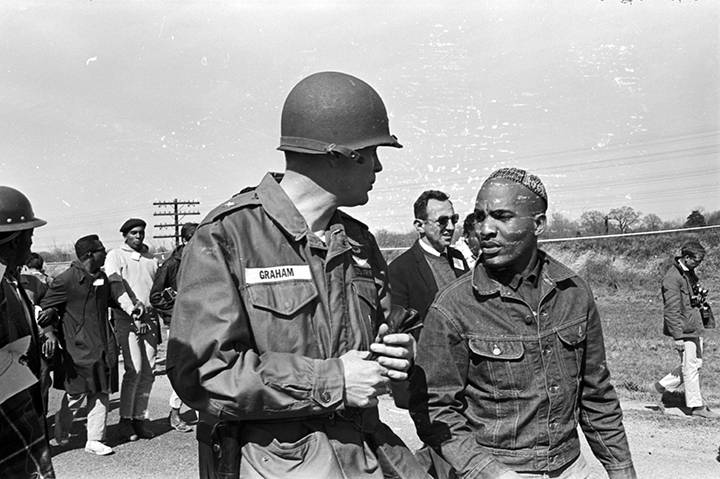

Major General Graham’s first interaction with the Civil Rights movement as an Alabama Guard leader occurred during the 1961 summer Freedom Rides. A multiracial coalition of activists converged in Alabama to protest continued segregation with civil disobedience. Local law enforcement and the Ku Klux Klan violently reacted to the Freedom Riders.

Graham escorted the Freedom riders throughout the state. As the Freedom Riders were settled on their bus in Montgomery (to go to Jackson, Mississippi) General Graham stepped on the bus and “said they were about to embark on a “hazardous journey. We have taken every precaution to protect you. I sincerely wish you all a safe journey.” Then he stepped off the bus.

The National Guard Association’s in-house publication, the summer 1961 National Guardsman, noted his professionalism in the face of the Klan and hostile state officials.

1963 marked the next major confrontation between General Graham and hardline Alabama Governor George Wallace, the defining moment of his National Guard career. Fulfilling election promises of “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever.” Governor Wallace attempted to stop black students from enrolling at the University of Alabama’s Foster auditorium by blocking the building entrance on June 11th.

An incident that immediately captured national media attention and became one of the civil rights movement’s critical battles. General Graham serving under federal orders at President Kennedy’s behest, was torn between his governor and Washington.

Wallace refused the entry of two African American students, Vivian Malone, and James Hood, into the auditorium despite orders from Justice Department officials accompanying the students, including an in-person demand from Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach. Wallace did not budge despite the high probability of violence erupting at the university and vocal condemnations from President Kennedy. Wallace’s stand worried officials in Washington who feared a political disaster and a constitutional crisis for the Kennedy Administration if the governor did not back down soon.

The Department of Justice implored General Graham, in his role as a federalized guardsman, to put an end to Wallace’s ploy. The General arrived on the campus later in the day; he approached Governor Wallace, saluted, and ordered him to stand down, saying, “Sir, it is my sad duty to ask you to step aside under the orders of the President of the United States.” Wallace eventually backed down and let the students into the building to complete their registration. [The National Guardsman: August 1963]

Graham’s willingness to stand up to his governor by enforcing federal law handed a significant victory to civil rights activists. The incident marked the beginning of the end of massive Resistance as the push for desegregation gained momentum throughout the 1960s. General Graham would also lead federal protection efforts for Martin Luther King’s March on Selma in 1965, eventually leading to Congress’s passage of the Voting Rights Act later that year.

George Wallace had a resilient political career throughout the 1960s and 70s despite the university standoff, representing the segregationist “Dixiecrat” wing of the Democratic Party. An assassination attempt while campaigning for President in the 1972 Democratic Primaries seriously wounded Wallace, ending his anti-integration efforts. During his recovery, Wallace moved away from his segregationist views, later serving as Alabama Governor again in the 1980s. Wallace also became friends with James Hood, the latter forgiving him for his segregationist policies.

General Graham concluded his Army career with retirement from the National Guard in 1970. Per the New York Times, he created a prominent Birmingham commercial real estate firm that still exists today.

His son commented to the Times that his father rarely spoke about his interactions with the Civil Rights movement but stated, “In later years, though, he looked back on it as a painful process that the region had to go through to bring it into the 20th century.” General Graham passed away in 1999 at 82, according to a Chicago Tribune obituary.