By William Roulett

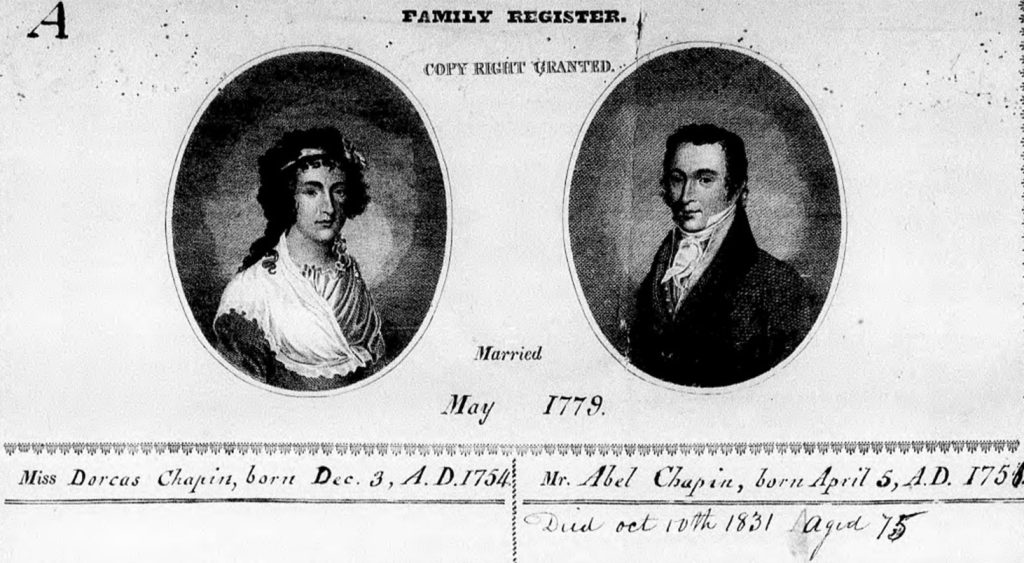

A Rendering of Abel Chapin from a Family Register

(Courtesy of National Archives)

At the National Guard Memorial Museum, we’re always researching something. It could be anything from an outside research request, future Minuteman Minute episodes, a new exhibit, or an existing one. Thanks to our access to the resources of other organizations and our ability to communicate with partners, we can learn more than ever before about something that has been in our collection for decades!

The National Archives and the National Park Service recently launched a crowd-sourced transcription campaign of their Revolutionary War pension files. In celebration of the forthcoming 250th anniversary of American Independence, they are seeking volunteers to transcribe case files of pension applications based on Revolutionary War service. Several items on display in our Militia Era Gallery are connected to veterans of the American Revolution and this project prompted us to see if we could learn anything new about their service.

In 1978, the Historical Society of the Militia and National Guard, now the National Guard Educational Foundation, purchased two sabers and other items from a private collector. The items were displayed in the National Guard Heritage Gallery, the precursor to the National Guard Memorial Museum. Those sabers belonged to the father and son Abel and Harvey Chapin of Massachusetts. They are each engraved with their owners’ dates of birth, dates of commission in the Massachusetts militia, dates of rank, and dates of death. A level of detail that seemed almost too good to be true 200 years later. Then, the Revolutionary War pension records corroborated and added to what we know about the Chapins.

Harvey Chapin saber (top) and Abel Chapin saber (bottom).

(Courtesy of NGEF Collection)

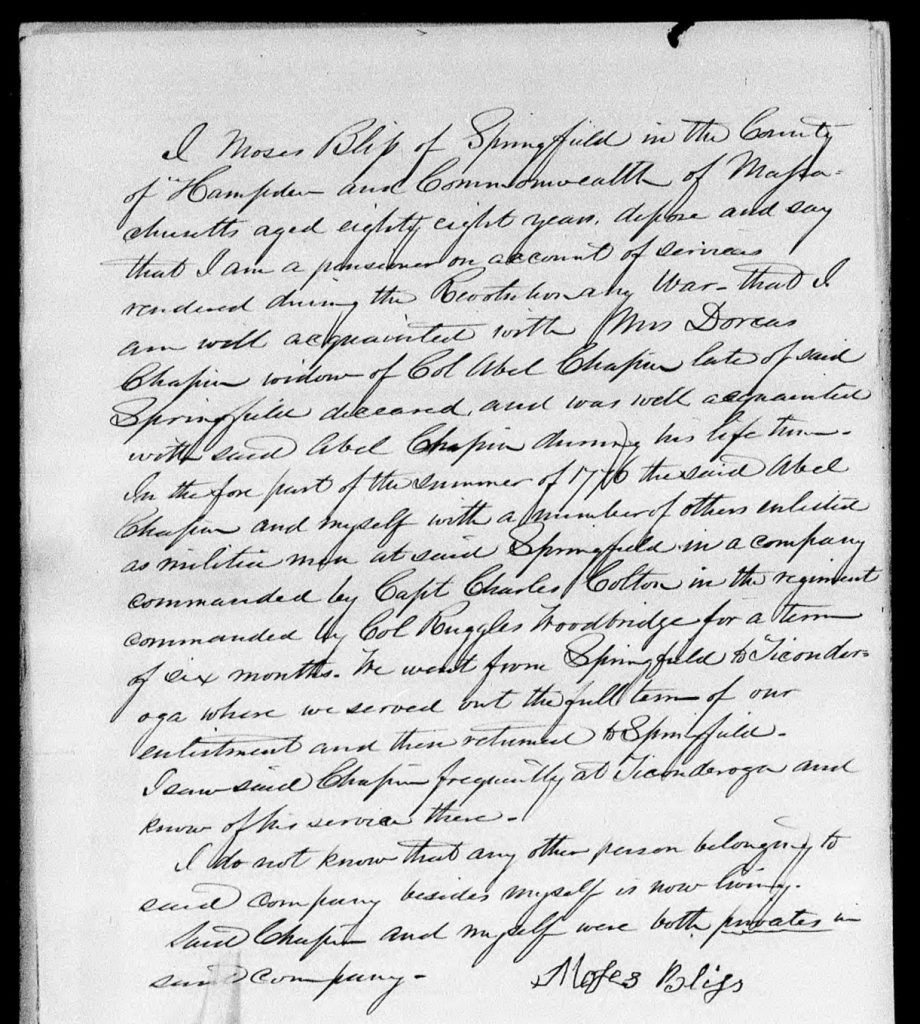

According to his saber’s inscription, Abel Chapin was commissioned by Massachusetts Governor John Hancock as a 1st Lieutenant in the 8th Company, 1st Regiment on July 1st, 1781. However, his pension records reveal this was not his earliest military service. In the summer of 1776, he enlisted in Springfield, Massachusetts for a term of six months, which took him to Fort Ticonderoga, New York. During the summer of 1776, American forces, who had been repulsed from an attempted invasion of Canada, reinforced Fort Ticonderoga in anticipation of a British counterattack. The details of Chapin’s service during that summer are known to us thanks to an affidavit given by Moses Bliss in May of 1841, almost 10 years after Abel had died.

Affidavit of Moses Bliss in support of Dorcas Chapin’s widow’s pension claim.

(Courtesy of National Archives)

Abel Chapin passed away on October 10, 1831, at the age of 75, having never filed for a pension. In July 1838, Congress passed an act (5 Stat. 303), granting 5-year pensions to widows whose marriages had taken place before January 1, 1794. This allowed Abel’s widow, Dorcas Chapin, to apply for a pension. However, pension seekers were required to provide their own proof of qualifying service in the form of eyewitness accounts given before justices of the peace as sworn affidavits. In the case of Dorcas Chapin, Moses Bliss’ account helped her claim the pension earned by her late husband’s service.

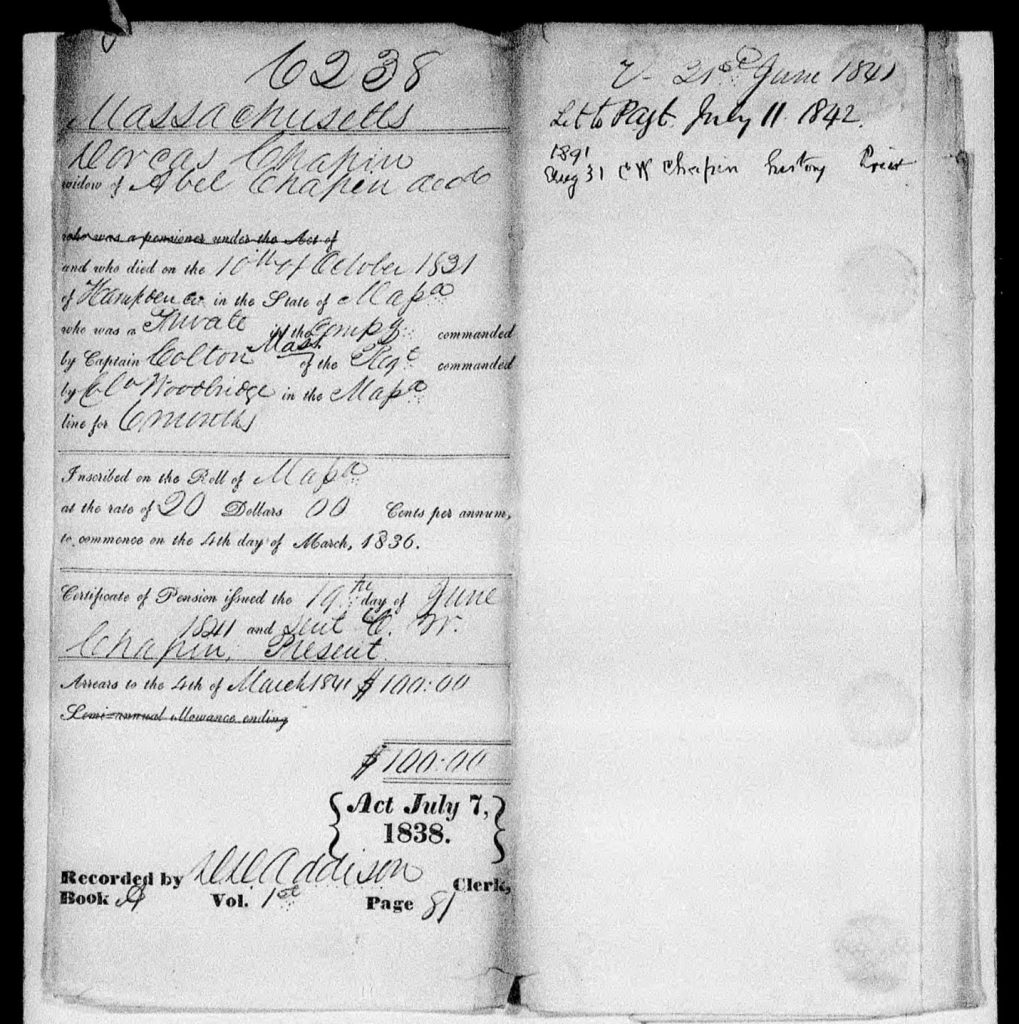

Approval of Dorcas Chapin pension

(Courtesy of National Archives)

Although illiterate, Dorcas submitted her application along with the Moses Bills affidavit and other documents in May of 1841. The following month it was approved at the amount of $20 dollars and back dated to March of 1836 because the Act of July 7, 1838, entitled her to a five-year pension. Dorcas received $100 in 1841, equivalent to $3,640.14 in 2024. Dorcas Chapin passed away soon thereafter, on July 30, 1841.

The mark of Dorcas Chapin is “X” in the center.

(Courtesy of National Archives)

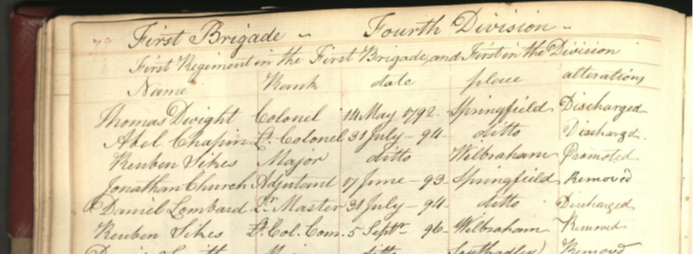

As with many Guardsmen, then and now, Chapin’s military career continued after a term of federal service. Thanks to the Massachusetts National Guard Museum and Archives, we can corroborate Abel’s militia service from 1781 to 1794. During that time, he attained at least the rank of Lt. Col., possibly full Colonel, and was likely called out during Shay’s rebellion.

Discharge of Abel Chapin from 1st Brigade, 4th Division,

Massachusetts Militia dated 31 July 1794.

(Courtesy of the Massachusetts National Guard Museum and Archives)

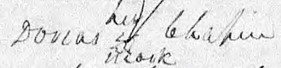

One of the truly remarkable documents we were able to access thanks to the National Archives is an annex to Chapin’s pension records, which features a likeness of him and his wife. It was commissioned by their son-in-law Eber Wright in about 1820 and contains a record of the marriage of Abel and Dorcas along with the births and deaths of their children. We can not only learn more about the service of a Revolutionary War veteran whose saber we display in our museum, we can put a face to a name almost 200 years after his death.

Chapin Family Register featuring Dorcas (left) and Abel (right).

(Courtesy of National Archives)