By Kevin Brown

“Captain Harry S. Truman: Citizen-Soldier”

(Courtesy of the National Guard Bureau)

The 35th Infantry Division of the National Guard has gained a place in the American imagination for its actions during the Normandy Campaign. Despite fame for Normandy gallantry, the 35th’s World War I history is relatively unknown compared to its WWII accomplishments.

The 35th Infantry Division was first organized into federal service in Oklahoma in the summer of 1917. The United States entered the First World War due to Imperial Germany’s unrestricted maritime warfare. The Division was nicknamed the “Santa Fe” after a cross representing the namesake western frontier trail leading through Missouri and Kansas, states which, with Nebraska provided the 35th’s units. The division adopted the Santa Fe Cross as its insignia for the same reason.

The 35th Infantry Division Patch

(Courtesy of the US Army Institute of Heraldry)

The 35th, under federal service, remained true to its Guard roots despite defense authorities’ efforts to create a unified army devoid of individualism. These efforts had the opposite effect, helping the Guard utilize volunteerism and patriotism to recruit locally.

The 35th Division’s Distinctive Unit Insignia (DUI)

(Courtesy of the Kansas Adjutant General’s Department)

Many of its enlisted men and officers hailed from the fringes of the Midwest, including Harry Truman, a young company-grade officer from Kansas City. Truman’s experiences as a Guardsman during WWI shaped his opinions on American society’s foreign and domestic challenges in the coming decades.

Harry Truman joined the National Guard because he had a lifelong desire to serve in the United States Army. Once completing his primary education, he applied to West Point but was rejected due to his terrible eyesight. After rejection, Truman joined the Guard instead, where he passed the physical by memorizing the eye exam chart. Some of Truman’s older family members, like his grandmother, disapproved of his military service due to her Civil War-era Confederate sympathies. His grandmother allegedly remarked, “Harry, this is the first time since 1863 that a blue uniform has been in this house. Don’t bring it here again.”

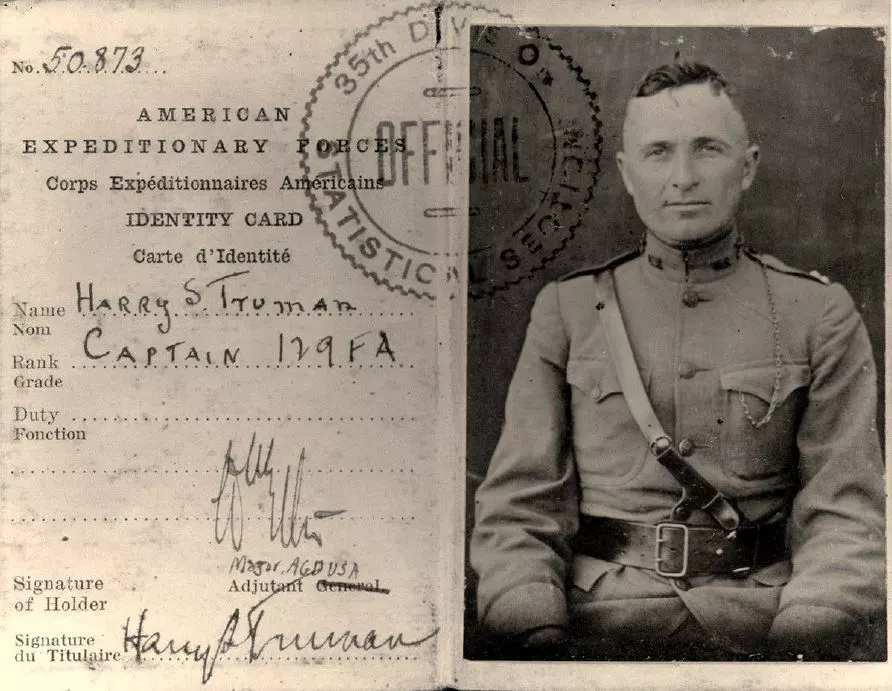

Truman became a career Guardsman beyond his initial 1905 enlistment in Battery B of Kansas City. He climbed the ranks of the Kansas City Artillery from private to corporal before being commissioned as an officer in 1911. Battery B was eventually redesignated the 129th Field Artillery Regiment in time for the 1916 Mexican Expedition; Truman was incorporated into the new unit in 1917, which joined the rest of the 35th for mobilization training at Fort Sill in Lawton, Oklahoma, in September 1917. Here, the 129th placed Truman in command of the regiment’s D Battery.

A Young Harry S. Truman in Uniform

(Courtesy of the National Guard Memorial Museum)

The 129th Regiment’s Battery D comprised men from an entirely different background than Truman; its ranks were filled mainly with Irish Catholic immigrants. The Battery had a reputation as a profane and hard-drinking unit when Lieutenant Truman took command. The young Lt. later remarked that he felt intimidated when taking the Battery’s command. However, he managed to motivate his non-commissioned officers to instill discipline and eventually gained the respect of his men. Battery D’s enlisted later believed that Truman’s effective leadership at Fort Sill saved American lives on France’s battlefields.

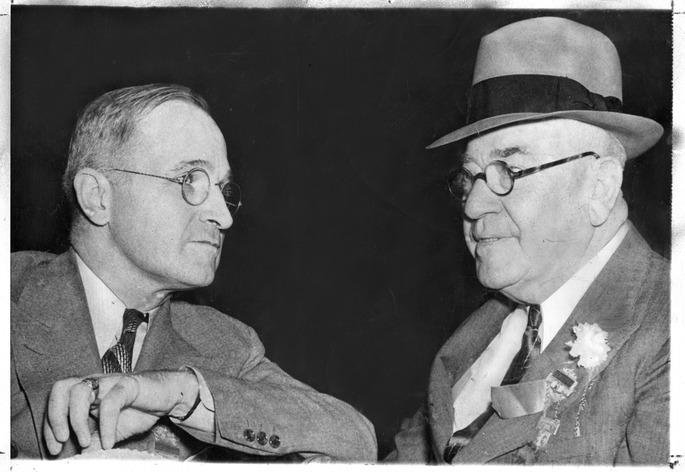

Lieutenant Truman worked alongside fellow artillery commander 2nd Lt. James Pendergast, also of Kansas City. Pendergast was the nephew of infamous political boss Tom Pendergast, who played a critical role in fostering Harry Truman’s post-war political career. Their service together in the 129th regiment helped launch Truman’s trajectory in Kansas City machine politics after the war, where Truman became known to his detractors as the “Senator from Pendergast.”

Truman with Kansas City Political Boss Tom Pendergast

(Courtesy of KC Yesterday: History of Kansas City)

Regimental leadership also put Truman in charge of the commissary. He was paired with a fellow Missouri Guardsman, Sergeant Eddie Jacobson from Kansas City, who ran a men’s clothing store in the city. Truman appreciated his assistance and business acumen.

Jacobson, who was the son of Jewish immigrants, was also a staunch Zionist who believed in a homeland for Jews in the Middle East. Both men became lifelong friends, and Jacobson’s viewpoints later influenced President Truman’s decision to recognize the newly created State of Israel in 1948.

The 35th Division embarked for France piecemeal in the Spring of 1918, when its elements sailed out of Philadelphia and entrenched themselves in the Vosges Mountains. The Vosges Front covered France’s frontier with Germany, including the 35th, the 42nd “Rainbow,” and the segregated 93rd Divisions.

Capt. Truman’s In-Theater Identity Card

(Courtesy of the National Park Service)

The 35th saw fighting during its deployment in the Vosges, where the men of Battery D enjoyed their first taste of combat “until the Germans “began to fire back.” However, despite his inexperience with combat, Truman rallied his troops and motivated them through their baptism of fire.

“Truman’s Battery” by Dominic D’Andrea

(Courtesy of the National Guard Bureau)

129th Artillery provided supporting fire for Allied forces during the Meuse Argonne offensive along the Cheppy-Varennes sector. During its initial bombardment of enemy lines, Truman’s regiment under the 35th’s 60th Artillery Brigade fired over 40,000 shells at German positions. American Expeditionary Force command specifically tasked Truman’s Battery with the support of Major George S. Patton’s provisional tank brigade. The leadership of now Captain Truman within the 129th’s Battery D proved decisive to America’s opening salvos in the Great War.

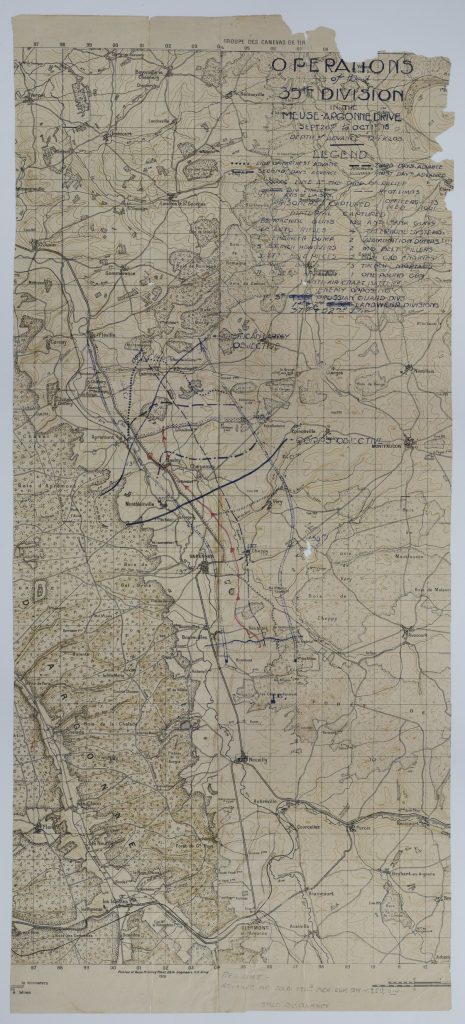

Map of the 35th ID’s Meuse-Argonne Offensive Sector, Sept-Oct 1918

(Courtesy of the Truman Library)

The entire 35th Infantry Division played a decisive role for American forces during the opening stages of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, beginning on September 26th, 1918. The Division’s advance along the Cheppy-Varennes front went smoothly at first since the initial bombardments caused German forces to retreat in chaos. However, the 35th’s elements ran into heavier German fortifications and better-organized resistance the further they moved into no man’s land. German landmines, combined with the damage done by their shelling, further slowed any gains the 35th made on the offensive’s first day.

American command staff failed to anticipate how clogged roads leading through no-man’s land would become as their artillery fire caused collateral damage while the 35th’s forward units faced counterattacks from hardened German positions. These traffic jams created further problems as most of the 35th’s artillery was on the road and not utilizing needed firepower against the German Army. The confusion caused by the fog of war had broken down communications and created friendly fire risks amid pockets of leftover German resistance.

Truman demonstrated resilient leadership by urging his men forward through the Argonne Forest. However, the future President was also careful not to push them beyond their limits, which caused a confrontation with his superior, Colonel Karl Klemm, the Battery’s artillery regiment commander. Since the offensive’s beginning, Col. Klemm demonstrated erratic behavior and kept pushing his units beyond their daily limits.

Colonel Karl Klemm

(Courtesy of Find a Grave.com)

Realizing that Col. Klemm was detached from reality, Truman risked insubordination towards the colonel in the interest of his men, who were already rendered ineffective by exhaustion. Capt. Truman ordered his unit to rest on the side of the road to rest for the night as his men and their horses could go no further. Despite facing a possible court martial for his actions, Truman won the respect of his men for standing up to his command in their best interest.

Truman demonstrated that he wanted to be a leader no matter the professional repercussions during his time in France. The Division’s artillery batteries were under strict orders to fire within their sectors, but Capt. Truman broke these orders when he believed doing so furthered the interest of his unit. For instance, while doing left flank reconnaissance, Truman spotted a German formation waiting to ambush his unit. He disobeyed orders and fired out of his sector on the German troops to preserve his own.

The AEF eventually pulled the 35th Division from the front lines on September 30th, 1918, due to casualties received from heavy German resistance after the Meuse-Argonne offensive’s first day. The Division saw little further action for the remainder of the war, which concluded with an armistice on the 11th hour of the 11th day of November 1918. After the conclusion of hostilities, the 35th was sent back to the United States in April 1919. The Division was demobilized at Camp Funston, Kansas, and reabsorbed into the peacetime National Guard.

Truman’s artillery battery amazingly suffered no fatalities during its deployment in France, which is even more impressive a feat considering that the Santa Fe Division sustained some of the heaviest losses among American units during World War I. Captain Truman’s men attributed their survival during the Great War’s hellish ordeal to his combat leadership skills. Their gratefulness later formed a crucial support base for Truman after the war, as he assimilated into civilian life and pursued bigger ambitions.

Upon returning home, Truman became involved with Kansas City’s Pendergast political Machine through his wartime connection service to the political boss’s nephew. The demobilized Truman won a Jackson County, Missouri judgeship while running a men’s clothing shop. Truman only doubled down on politics after his business failed during the Great Depression. He leaned in on his political machine involvement and military connections to win a U.S. Senate seat as an FDR-supporting New Deal Democrat in 1934.

Truman would eventually become FDR’s Vice President in 1944, in the middle of World War II, and eventually President. He relied upon his First World War experiences to make controversial decisions such as dropping the atomic bomb on Japan, desegregating the military, or defending South Korea from Communist aggression.

(Courtesy of the Truman Library: Dedication of the Original NGAUS Building in 1959)

The 35th’s combat exploits didn’t end with the Great War. Nearly twenty years later, it would mobilize back into service to face Fascist aggression. This Division joined the legendary 28th and 29th divisions at St. Lo in a pitched battle against Hitler’s Third Reich in the days after June 6th, 1944, playing a deciding role in the Normandy Campaign. The 35th Division later pierced the Siegfried line, helping land the final defeating blows against Hitler before returning home victorious in the Fall of 1945.