Next time you visit the museum, make sure to stop by our new temporary exhibit celebrating the 60th anniversary of National Guard service during the Korean War. The exhibit focuses on one individual whose work with Korean factory workers during the war made a lasting impression.

Maj. Samuel C. Crooks, a Rhode Island Army National Guardsman, deployed to Korea in 1948 to serve with the Korean Military Advisory Group, or KMAG. Serving as an individual officer rather than with a unit, Crooks helped run a clothing factory that provided items for the Korean military.

As a civilian, Crooks, who was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland, was vice president and general manager of the Collyer Insulated Wire Company of Lincoln, R.I. Working with his Korean counterpart, Col. Kim Il Ki of the Republic of Korea Army, he was able to successfully manage the factory and its large civilian workforce for the Korean army’s 1079th Quartermaster Company.

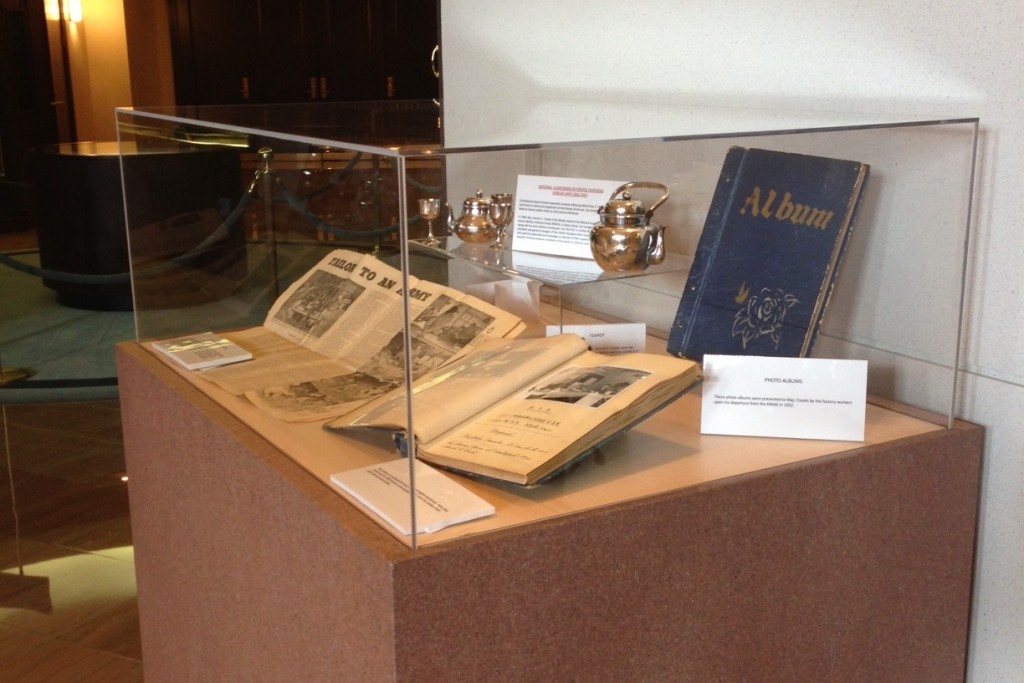

Before he left the country, the workers presented him with photo albums of his time at the factory. He was also given a lovely silver teapot and a silver pot and cups for drinking sake, an alcoholic beverage made from fermented rice. Both sets were engraved to commemorate his tenure with their factory.

These items were donated in 2011 to the National Guard Memorial Museum by Bruce P. Crooks, the major’s son and also a member of the Rhode Island Guard. The artifacts are on display now in a temporary exhibit at the museum.

Crooks enlisted in the Rhode Island Guard during World War II. His service in the war included a stint in the active component Army. After the war, he returned to the Guard and was shipped to Korea to help at the factory.

The factory was quickly caught up in the hostilities on the Korean Peninsula. Established in 1948 in Seoul, it was threatened by North Korea’s first invasion across the 38th parallel in June 1950. The workers retreated to Pusan. In September, they returned to Seoul but found only a demolished factory.

They rebuilt the factory, but suffered a second routing by Chinese communist forces in December. Once again, they pulled up stakes and headed for Pusan, deciding to stay there and use what machinery they could salvage to start the factory anew.

They returned to the work of fabricating fatigues, padded uniforms and other badly needed textiles. The factory eventually had 1,200 workers and 450 sewing machines. They were so successful that the Korean army and the KMAG started a technical trade school which thrived for several years.

The good work of Crooks did not go unnoticed. In June 1952, the factory was the subject of an article in Stars and Stripes, the military’s newspaper. Written by Pfc. Jack L. Stein, the article noted that Crooks aided “the Koreans with his knowledge of mass production methods similar to those employed in the United States.” An original edition of this newspaper is part of the museum exhibit, open to the pages carrying the story of Crooks and the factory.

Upon his return to America, Crooks was promoted to lieutenant colonel and commanded a Rhode Island Army National Guard quartermaster unit.

In the exhibit, one photo album is open to a page containing a photo of Crooks and Ki sitting at a desk as they perform their administrative duties. Included in the collection, but not displayed, is a hand-typed autobiography by Crooks of his time in Korea, which concludes with, “In many ways, this factory is symbolic of the South Korean people and the independence and freedom for which they are striving. It is a monument to their perseverance, ingenuity and courage in this struggle for democracy. . . .The early stand of these people against overwhelming odds at Seoul is an echo that is reminiscent of the stand in America by the farmers and minutemen at Lexington in the not-too-distant past.”