By Kevin Brown

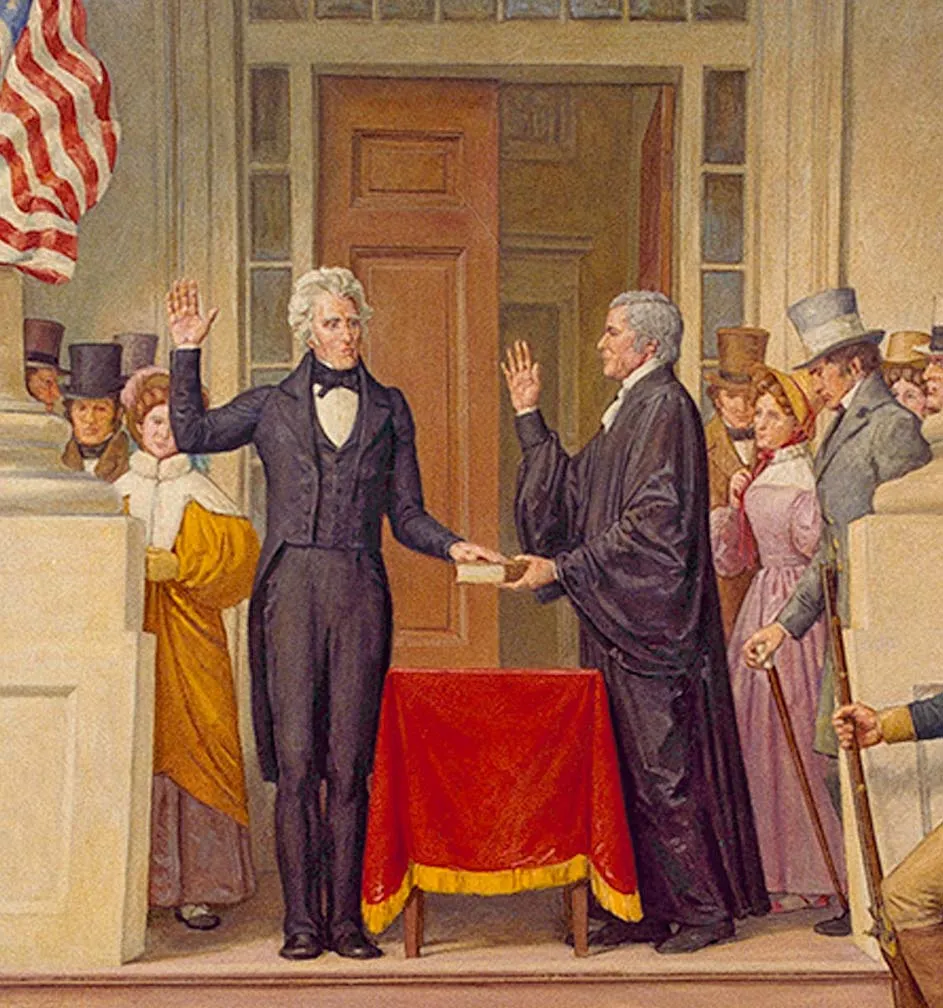

Andrew Jackson leading his troops during the Battle of New Orleans-January 1815

(Courtesy of Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage)

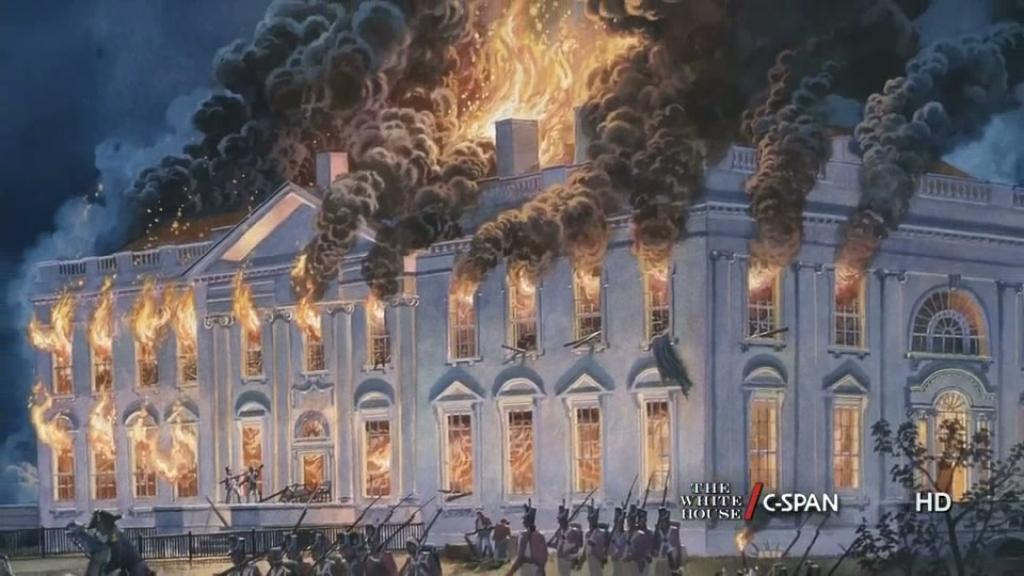

The War of 1812, launched by the James Madison Administration to expand territory and prevent British impressment of American sailors, ended in disappointment. The British were able to mobilize the forces of their empire to inflict painful defeats upon the young American Republic, including the destruction of the White House.

British troops razing the White House in August 1814.

(Courtesy of C-Span)

Both sides were eager for peace by the fall of 1814 when American and British delegations signed the Treaty of Ghent in Belgium on Christmas Eve. The Treaty restored the pre-war status quo, dictating the return of all captured prisoners and the resumption of trade between the two belligerents. In an era that lacked today’s technology, news of the peace treaty did not reach North America in time to prevent further fighting.

John Quincy Adams meets with British Representative Lord James Gambier in modern day Ghent, Belgium.

(Courtesy of PBS)

British Secretary of War Henry Bathurst was skeptical that President James Madison would honor any peace treaty. He believed the pre-war Louisiana Purchase was not legitimate and that the populations of that newly acquired territories did not support the American government. Bathurst also resented the American government’s tolerance of slavery and felt Britain could do more to combat it once Napoleon was defeated in Europe.

Bathurst issued orders to Major General Sir Edward Packenham in the months before Ghent to continue the war against the United States until a treaty was ratified by the Americans. Major General Packenham, regarded as one of the top commanders in the British Army, set out for New Orleans soon after receiving his orders. He was not only a respected career British Army officer but the brother-in-law of Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington.

Maj. Gen. Edward Packenham

(Courtesy of the US National Park Service)

Packenham was unenthusiastic about his new assignment, chosen only to replace Maj. Gen. Robert Ross, who was killed in Baltimore earlier in the year. Packenham would rendezvous with Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, the senior British commander in the theater. Packenham prided himself on his duty to the Crown and being a gentleman.

Tennessee militiaman and rising star Andrew Jackson was settling into New Orleans by December 1814 after ensuring American dominance over the deep South during the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in Alabama. Jackson had served in southern militias during the Revolutionary War and rapidly rose in ranks when the War of 1812 broke out. His troops called him “Old Hickory” due to his toughness.

Jackson’s pragmatic leadership forced him to put his support of slavery as an institution aside. He aggressively recruited freed black men with promises of equal pay and recognition, in stark contrast with most plantation owners, who forced their slaves to fight for the American cause without any compensation for their service. Though Jackson’s words were often inconsistent with his actions, keep black troops out of New Orleans to avoid agitating the city’s white residents, and eventually reneged on his promises of emancipation.

General Jackson also towed a tough line toward civilians in New Orleans. He put the city under martial law shortly after arriving there. Jackson, ironically, shared the same views as the British in that he didn’t see Spanish or Creole communities existing in New Orleans as loyal to the United States. Old Hickory even imprisoned a Federal Judge who ruled his actions were unconstitutional.

Meanwhile, Jackson constructed defensive lines outside New Orleans to take on the superior British attackers. Old Hickory instructed his roughly 4,000-strong force to fashion forts made of clay and cotton bales along the city’s Mississippi River approaches, obstructing navigation of the waterways. The Tennessee Militiaman diversified his troop strength by not only employing African Americans but also enlisting Jean Lafitte’s band of pirates, whom Jackson termed ” hellish banditti,” to harass the Royal Navy along the Gulf Coast.

Infamous Gulf Coast Privateer Lean Lafitte.

(Courtesy of the American Battlefield Trust)

Combined British forces under Admiral Cochrane were massing off New Orleans’s coast, awaiting reinforcements’ arrival under Maj. Gen. Packenham. In the meantime, Cochrane’s forces engaged in several naval skirmishes with the Americans, culminating in an altercation within Lake Borgne outside of New Orleans on December 14th.

Admiral of the Blue Sir Alexander Cochrane

(Courtesy of the UK National Portrait Gallery)

Despite a quick British victory within Lake Borgne, disinformation from prisoners of war asserting that Andrew Jackson’s forces were much more formidable than previous reports gave attacking commanders cause for concern. These rumors undermined British confidence in a quick victory.

Delays and miscalculations plagued Packenham’s journey from Britain to America. Initially planning to meet with existing flotillas in Jamaica on his way, Pakenham did not arrive in New Orleans until Christmas Day. Frustrated by his transatlantic journey and the inability of the existing British forces to capture New Orleans, he landed his troops at the Chalmette Plantation right outside the city.

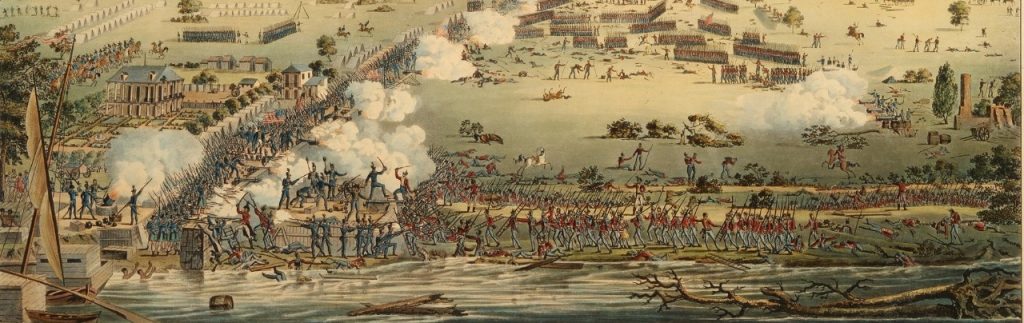

The British Army became bogged down at the plantation between December 27th and early January after repeated head-on attacks on Jackson’s hardened positions along the banks of the Mississippi River. Andrew Jackson’s rudimentary fortifications provided a significant force multiplier to his much smaller army.

Fighting at Chalmette Plantation.

(Courtesy of the US Naval History and Hertiage Command)

Maj. Gen. Packenham opted for an even larger frontal assault on Chalmette despite previous failures. This time it turned out no different as Tennessee and Kentucky militiamen within the improvised forts decimate the advancing British Redcoats: Packenham and his second in command, Maj. Gen. Samuel Gibbs were both mortally wounded in the failed attack.

A Kentucky soldier commented, “When the smoke had cleared, and we could obtain a fair view of the field, it looked at first glance like a sea of blood. It was not blood itself but the red coats in which the British soldiers were dressed. The field was entirely covered in prostrate bodies.”

British forces promptly embarked on their ships after the defeat, with the Royal Navy retreating into the Gulf of Mexico. The Battle of New Orleans cemented America’s dominance of its newly acquired territory and Andrew Jackson’s reputation.

Andrew Jackson emerged as a newfound American hero of the final battle of the War of 1812. Jackson used his wartime fame over half a decade later to run for the Democratic nomination for President. He would eventually win a vicious Presidential contest against John Quincy Adams, becoming one of American history’s most influential and controversial presidents.

Andrew Jackson taking the oath of office upon his Presidental inauguration in March 1829.

(Courtesy of Encyclopedia Britannica)