By Kevin Brown

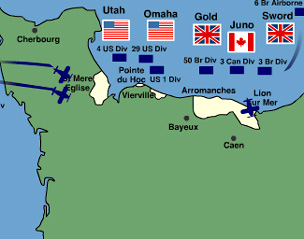

The National Guard’s 29th Infantry Division stands out for its service at Omaha Beach on D-Day, June 6th, 1944. The 29th was dubbed the “Blue and Gray,” represented in a yin-yang symbol patch, because the Division traced its history to Union and Confederate Civil War units. In World War I, the 29th participated in the Meuse–Argonne offensive, ending the bloody conflict. Upon returning home in 1919, the decorated 29th was demobilized, and its citizen soldiers returned to civilian life.

(Courtesy of the 29th Infantry Division Association)

The 29th Division was activated in February 1941 by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in response to Hitler’s Blitzkrieg. Former National Guard Association President Lieutenant General Milton Reckford oversaw the Division’s training drills at Maryland’s Fort Meade before shipping off to Britain. While there, the 29th trained as one of the National Guard Infantry Divisions selected to participate in the Operation Overlord-Day landings.

(Courtesy of the American Legion)

Allied planners selected the 29’s 116th Infantry Regiment to spearhead the assault on Normandy’s Omaha Beach. Allied intelligence considered Omaha the most challenging landing beach due to its rocky terrain and high bluffs, providing defenders an advantage over any attacking amphibious force. Allied command divided the 116th’s responsibility for the Beach into four sectors Easy Green, Dog Red, Dog White, and Dog Green.

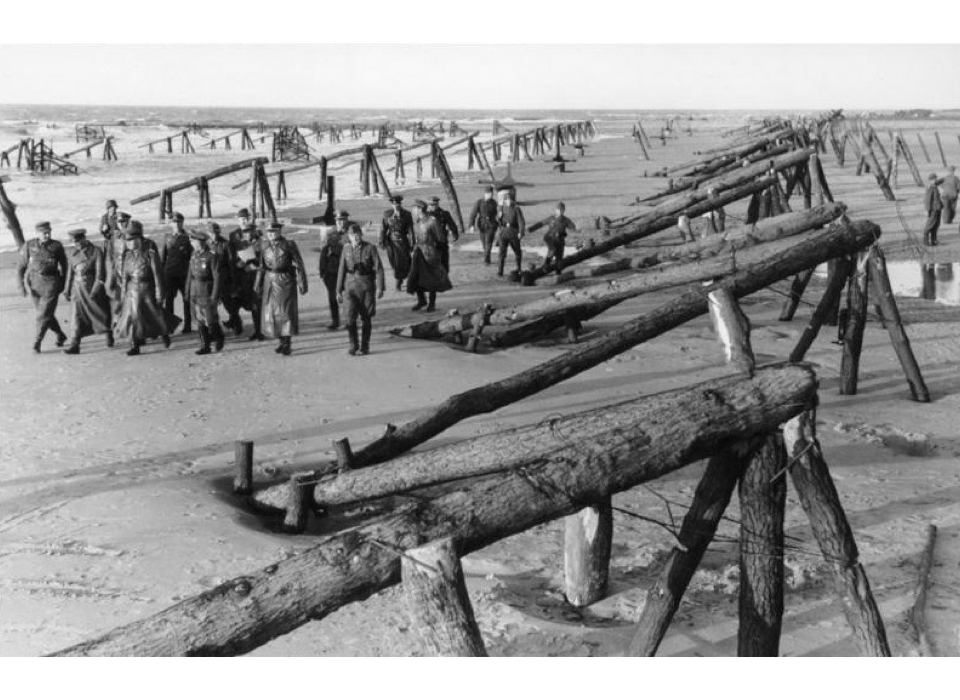

German Wehrmacht commanders viewed France as a safe space for their forces to recover from the horrific fighting against the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front. The defense of Omaha fell on the 352nd Infantry Division, consisting of hardened Eastern Front veterans. The Third Reich’s forces at other Normandy beaches were mainly “Static Divisions.” These units consisted of forcibly conscripted Soviet and Eastern European men poorly trained, led, and equipped.

Most of the 29th Division embarked from Trebah in Cornwall for the shores of Normandy. Due to the unit’s unique mission, the Virginia National Guard’s 116th Regiment left for France separately from the rest of the Division on June 3rd, 1944. The 29th disembarked into their Higgin’s Boats off the coast of France in the early hours of June 6th, 1944, entering the unknown.

A bombardment operation targeting German positions at Omaha Beach was unsuccessful, alerting the Wehrmacht to an incoming offensive. Heavy winds and rough seas significantly complicated the landing for the 116th. Poor conditions caused landing craft to sink, losing many men. Most of the 116th’s tanks and assault vehicles struggled to reach the shore. The bombardment of Omaha also failed to create cover and concealment for troops landing on Omaha, leaving them vulnerable to German firepower.

The first-wave companies of the 116th Regiment were either completely wiped out or missed their assigned Omaha landing sectors. Strong morning ocean currents, fires, and obstacles on the Beach complicated operations for American service members struggling to gain a foothold onshore. This initial chaos on D-Day created a situation where exhausted troops had to charge over 200 yards up dangerous beaches to escape German fire.

Problems were compounded by the arrival of the second wave, facing the same conditions as the initial assault. The three reinforcing companies of the 116th’sFirst Battalion faced heavy fire, disorientation, and fatalities among company-grade leadership. Some of the 29th’s men sought refuge along the walls of the beaches’ embankments.

At the behest of the 29th‘s Deputy Commander Brigadier General Norman Cota, the remaining troops on the Beach finally managed to storm Omaha’s Bluff and break through the German Army’s defensive lines.

Resistance was also beginning to wear down in Omaha’s various sectors as German forces ran low on ammunition and stamina. Allied troops at other Normandy Beaches like Juno, Gold, Utah, and Sword were also pushing inland. German defenses were thrust into chaos due to Allied paratrooper landings across Normandy’s interior, diverting critical Wehrmacht troops from Omaha Beach. The overwhelming force deployed at Normandy and the Third Reich’s increasingly desperate strategic situation by the spring of 1944 made defending Omaha as tricky as capturing the Beach.

The elements of the 29th Division began establishing a beachhead despite the heavy casualties endured while landing. The 121st Combat Engineer Battalion of the Washington DC National Guard managed to secure the area directly beyond the Beach despite suffering significant losses, clearing the way for the rest of the division’s elements to pierce German lines. Spearheaded by the 116th Regiment, the 29th Division captured Omaha entirely by mid-afternoon despite delays caused by holdout enemy positions.

However, the 29th Division still had bloody fights ahead even after the Omaha landings. The Division faced fierce fighting in Normandy’s agricultural hedgerow country as it advanced toward the important crossroad town of St. Lo, commencing battle with Hitler’s forces on July 7th, 1944. The North Carolina-based 30th and Plains state-centered 35th Infantry Divisions joined the 29th to take the critical town.

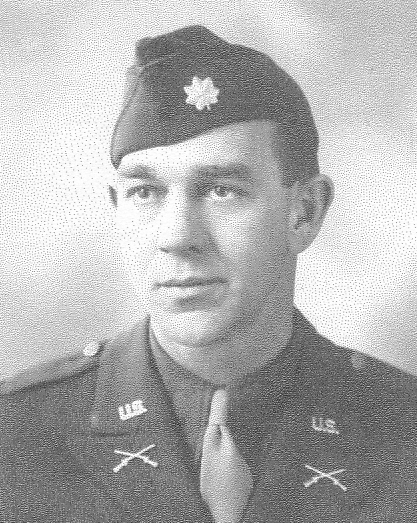

The 29th Division suffered further fatalities from German artillery strikes and fierce house-to-house fighting within St. Lo. One prominent American fatality of the action was career Virginia Guardsman Major Thomas D. Howie. Howie single-handedly led his troops to rescue their division’s 2nd Battalion, where they also successfully broke through German lines at Martinsville. A mortar round killed Major Howie shortly after radioing 29th Commander Charles Gerhardt, “See you in St. Lo!”

(Courtesy of the Staunton News Leader)

On the anniversary of D-Day, stars and Stripes war correspondent and famous media personality Andy Rooney remarked .“More American soldiers were killed taking Saint Lo than on the beaches. A major named Tom Howie was the battalion leader that captured Saint Lo. At least he was the leader until he was killed just outside town. After he died, his men picked him up, carried him into town, and placed him on a pile of stones that used to be a church wall. I guess there never was an American soldier more honored by what the people who loved him did for him after he died. Undoubtedly, Thomas Howie was a charismatic leader, a courageous soldier, and a man of outstanding character.”

The 29th and its various elements engaged in heavy fighting throughout France for the rest of 1944. Though the 29th did not participate in the Battle of the Bulge, the Division led efforts directly south of the Ardennes Forest to cross the Rhineland’s Roer River, which swept across central Germany.

During the push through Germany, the 29th Division also liberated Dinslaken-a slave labor camp that was part of the Final Solution. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum considers the Division a Liberating unit.

The Division even had a chance to rendezvous with Soviet forces at the Elbe River, enthusiastically exchanging greetings and wartime memorabilia.

After Germany’s unconditional surrender to the Allies in May 1945, the 29th Division settled into post-war occupation duties.

The 29th Division’s personnel earned high-level decorations throughout the Western European campaign, including two Medal of Honor recipients and numerous other citations. Films like The Longest Day (1962), Saving Private Ryan (1998), and segments of HBO’s Band of Brothers series pay homage to the 29th Division’s actions at Omaha Beach.